Over a decade ago, by decree of the former Minister of Culture Farruco Sexto, the collections of Venezuela’s national museums were merged with no regard to the specific focus or mission of each institution. The authorities also decided to dispense with the roles of curators and specialists.

I wondered about the current situation at the Galería de Arte Nacional; the Museo de Bellas Artes; Museo Alejandro Otero; Museo de la Estampa y del Diseño Carlos Cruz Diez; Museo de Arte Popular, Museo de los Niños; Museo Arturo Michelena; Museo de Ciencias Naturales; and Museo del Oeste Jacobo Borges, among other art institutions located in the greater Caracas area.

It is also difficult to picture the fate of museums in the rest of the nation, in cities such as Ciudad Bolívar, Mérida, Maracay, Maracaibo, and Pampatar.

Gabriela Rangel asks in her January 30, 2022, hyperallergic.com article the following:

“Have these institutions acquired any works by Venezuelan artists produced after 2000? How many Venezuelan artists have fled the country?”

“How many Venezuelan curators and scholars live abroad and hold positions in museums in the United States or wherever they have been taken in?”

“Which contemporary Venezuelan artists have had exhibitions in the country and how many publications about their work have been printed?”

Rangel adds that the answer evokes a crepuscular verse by Kafka: “You are forever speaking of death, and not dying.” But the swan song of Venezuelan museums has a presence that is a discrete and modest counterpart to the absence of public spaces dedicated to the visual arts.

“The audience, and what’s left of the educated middle class still wading in a few puddles of oil, stopped visiting museums, relocating the ritual of visiting the muses to spaces situated in a few residential shopping malls—where art exhibitions have mutated to the kunsthalle model or exist as temporary shows held by commercial galleries.”

Presentation

How to understand the current situation of art museums in Caracas? And how to imagine the fate of museums in the rest of the nation, in cities such as Ciudad Bolivar, Merida, Maracay, Maracaibo, and Pampatar? What do they symbolize today?

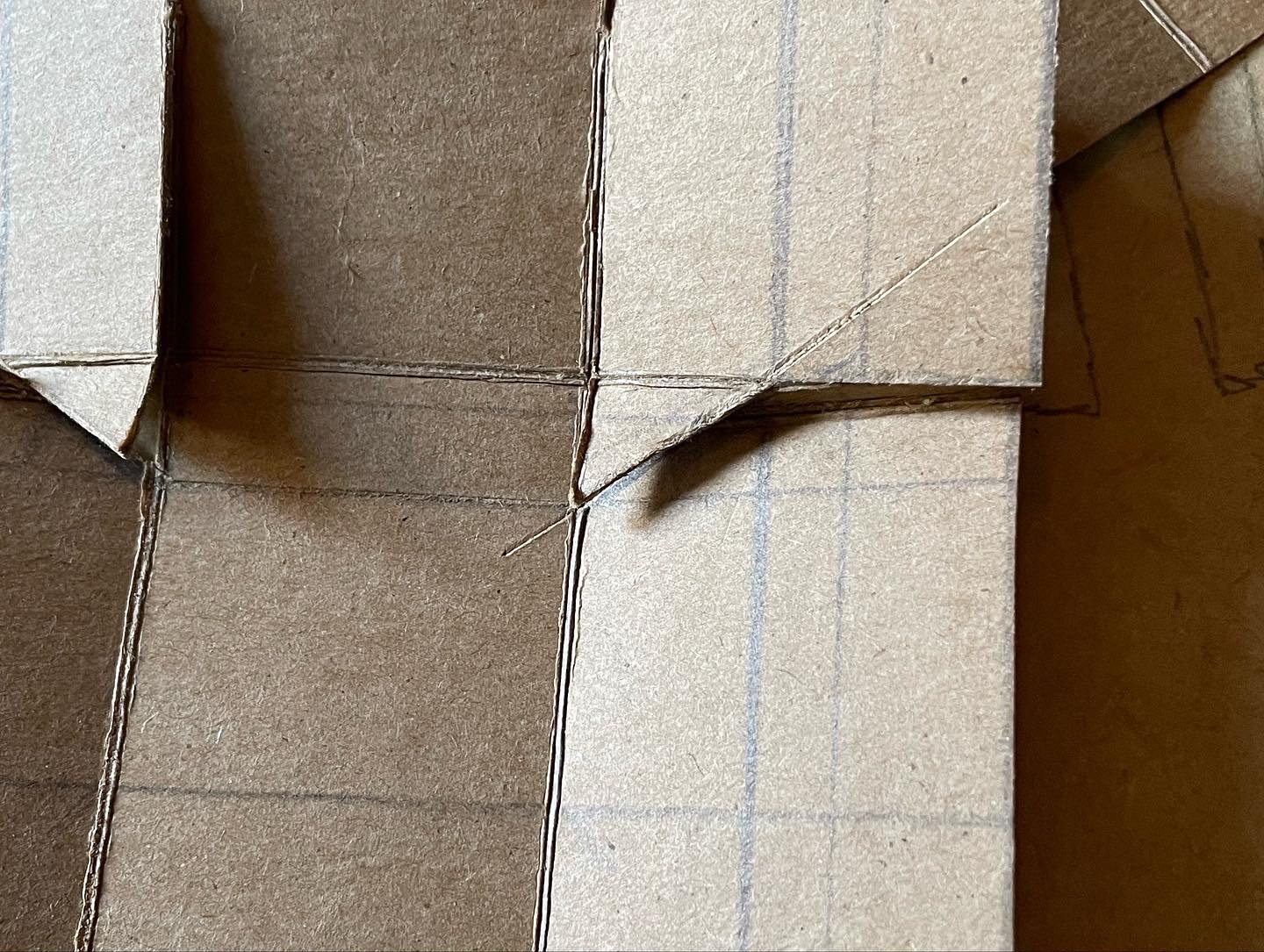

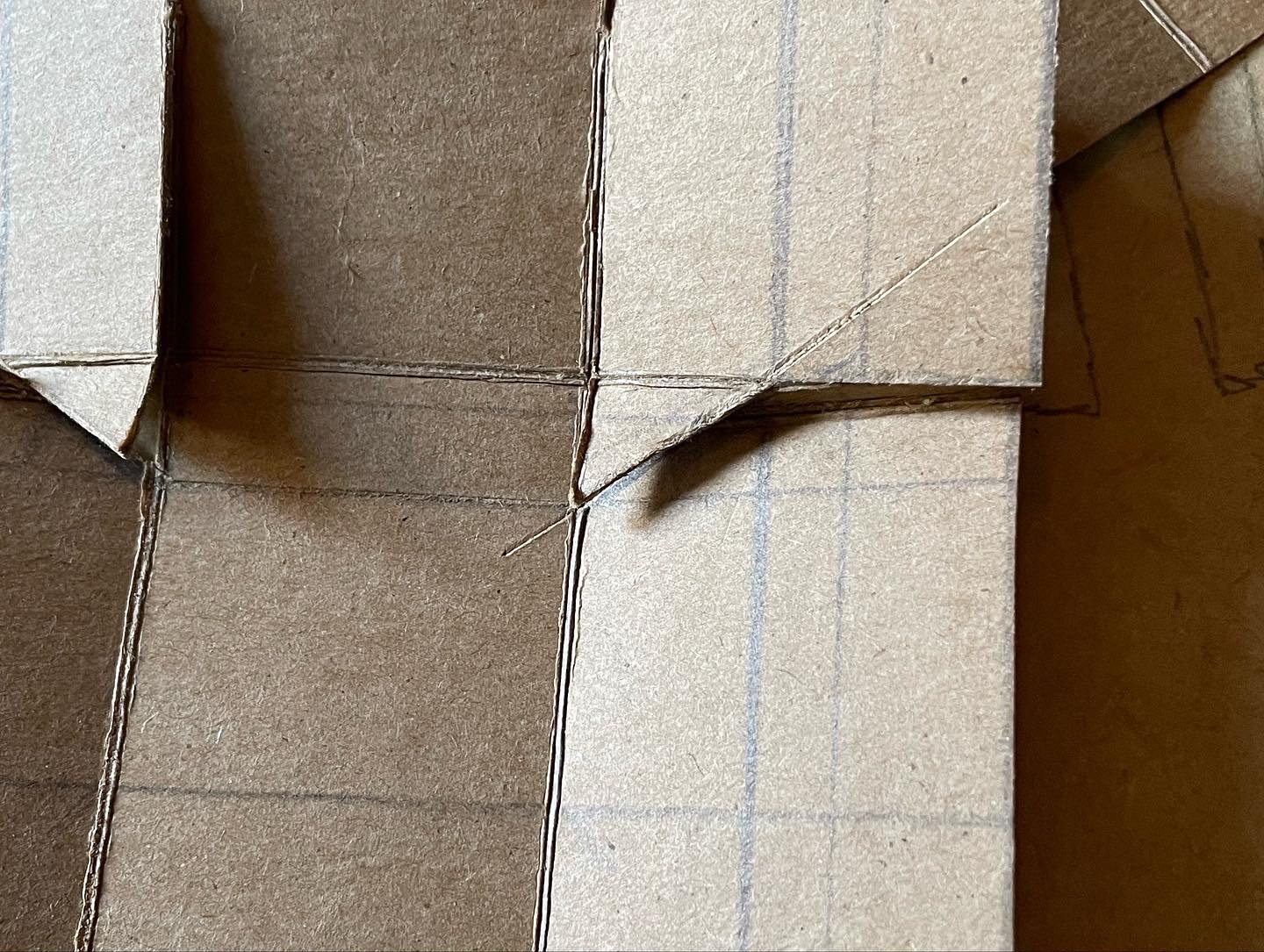

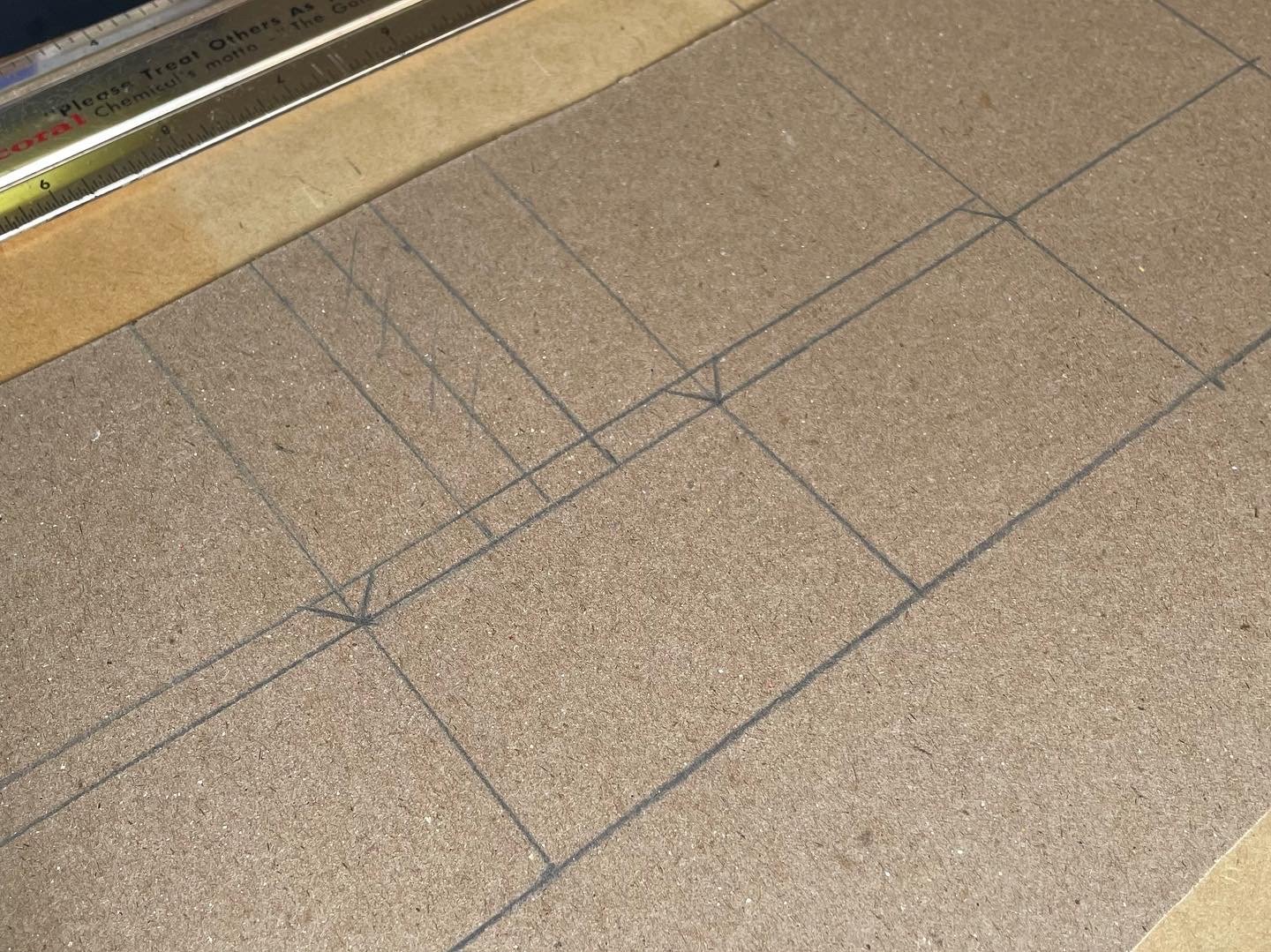

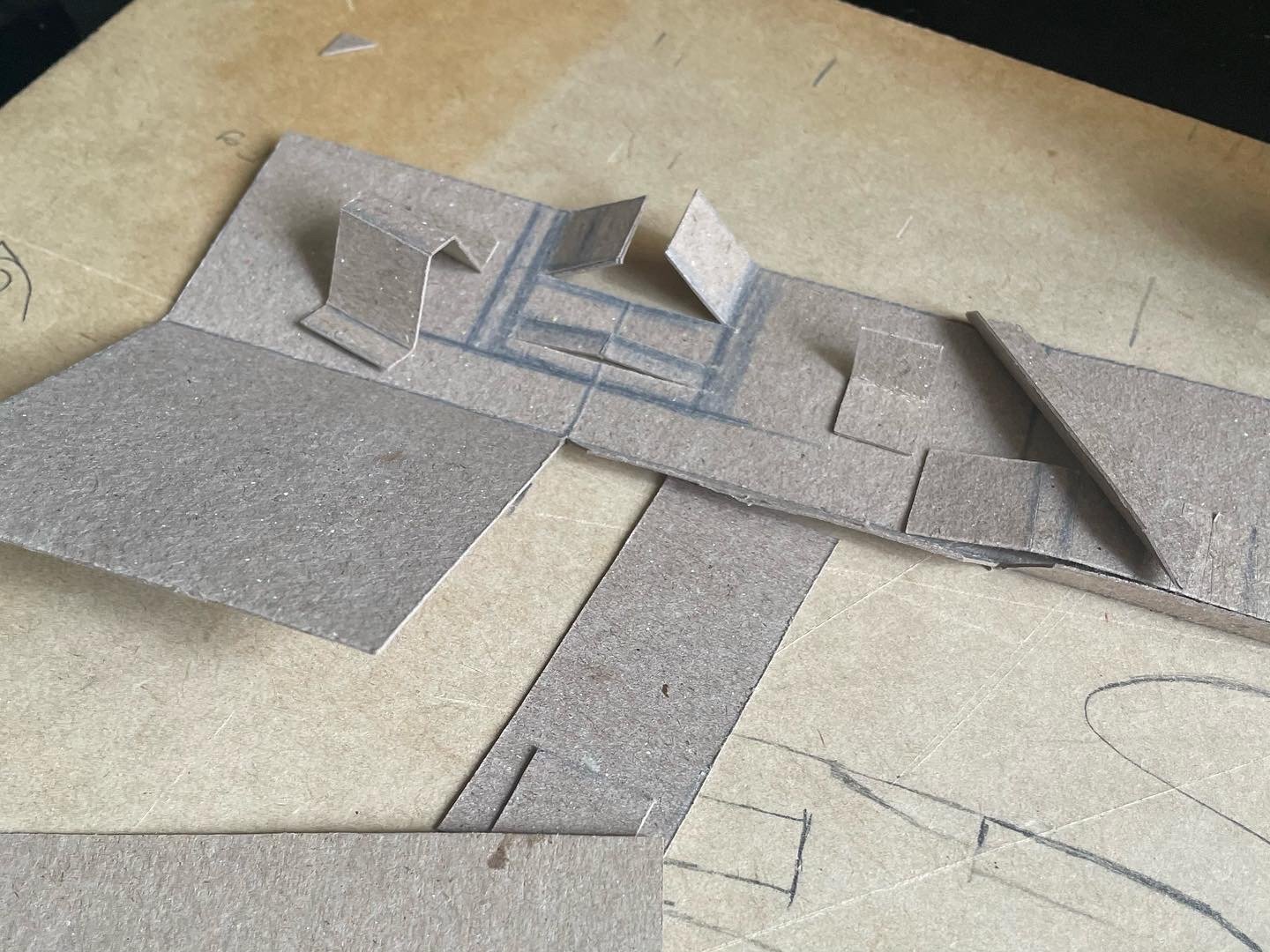

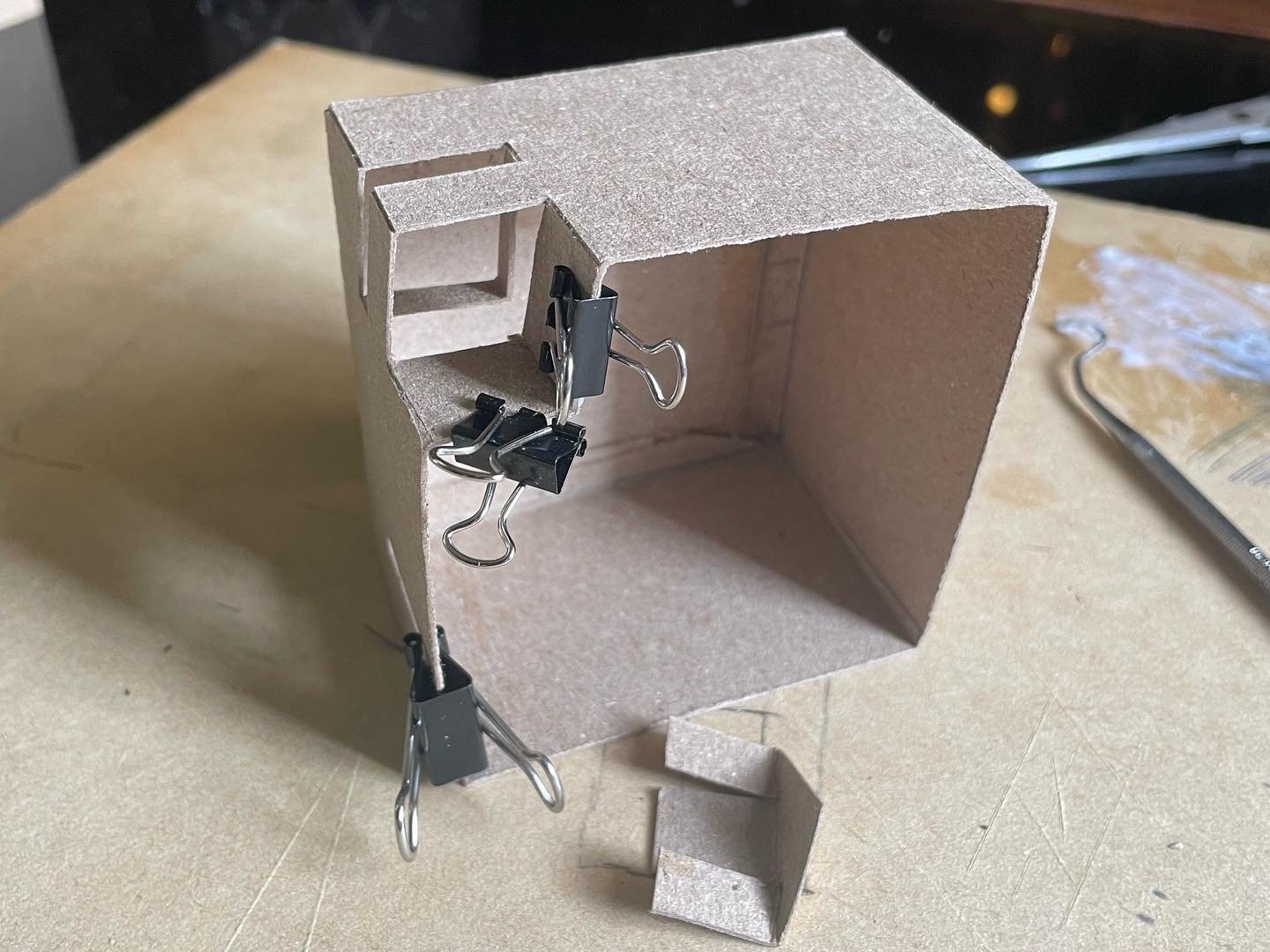

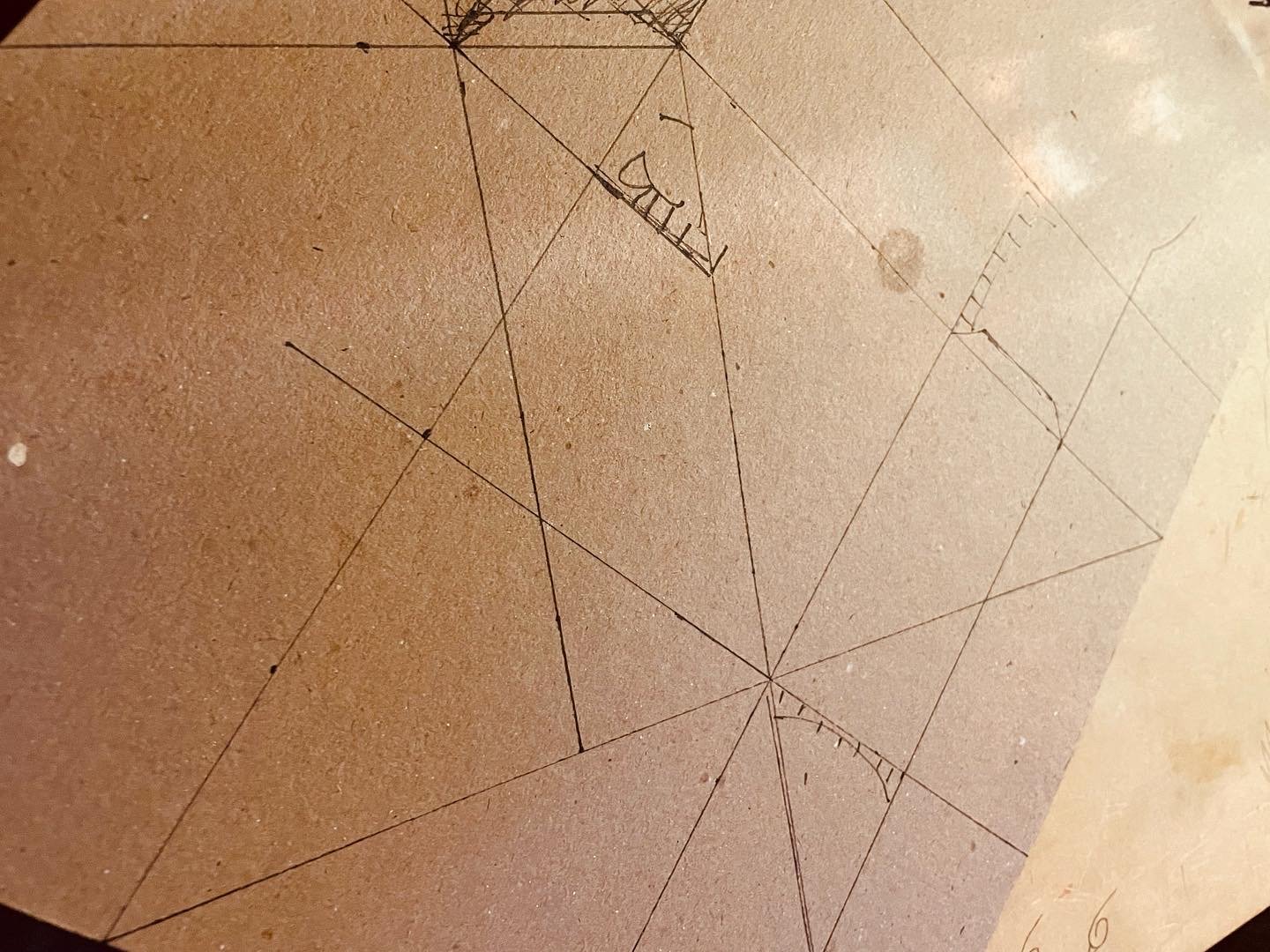

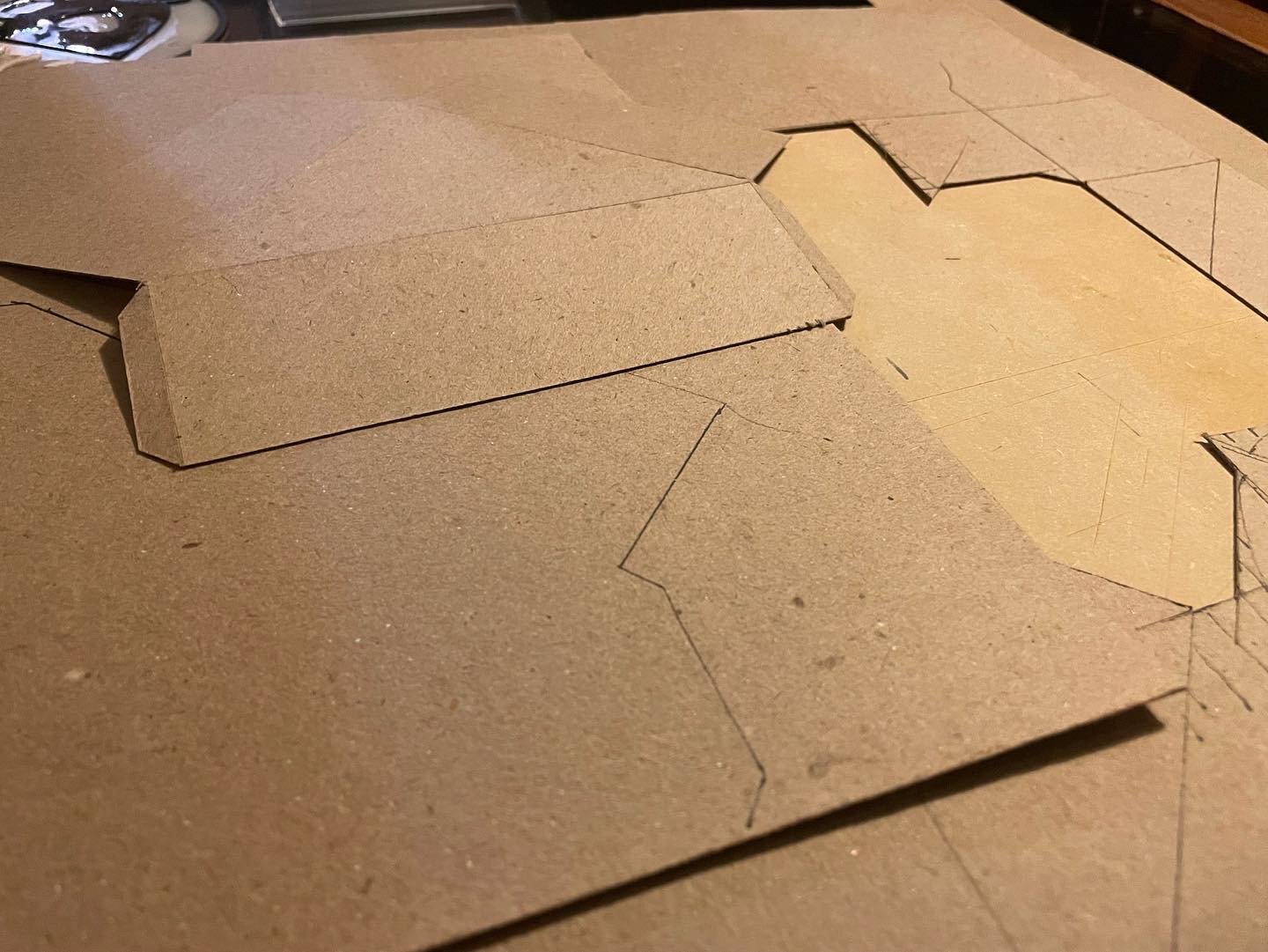

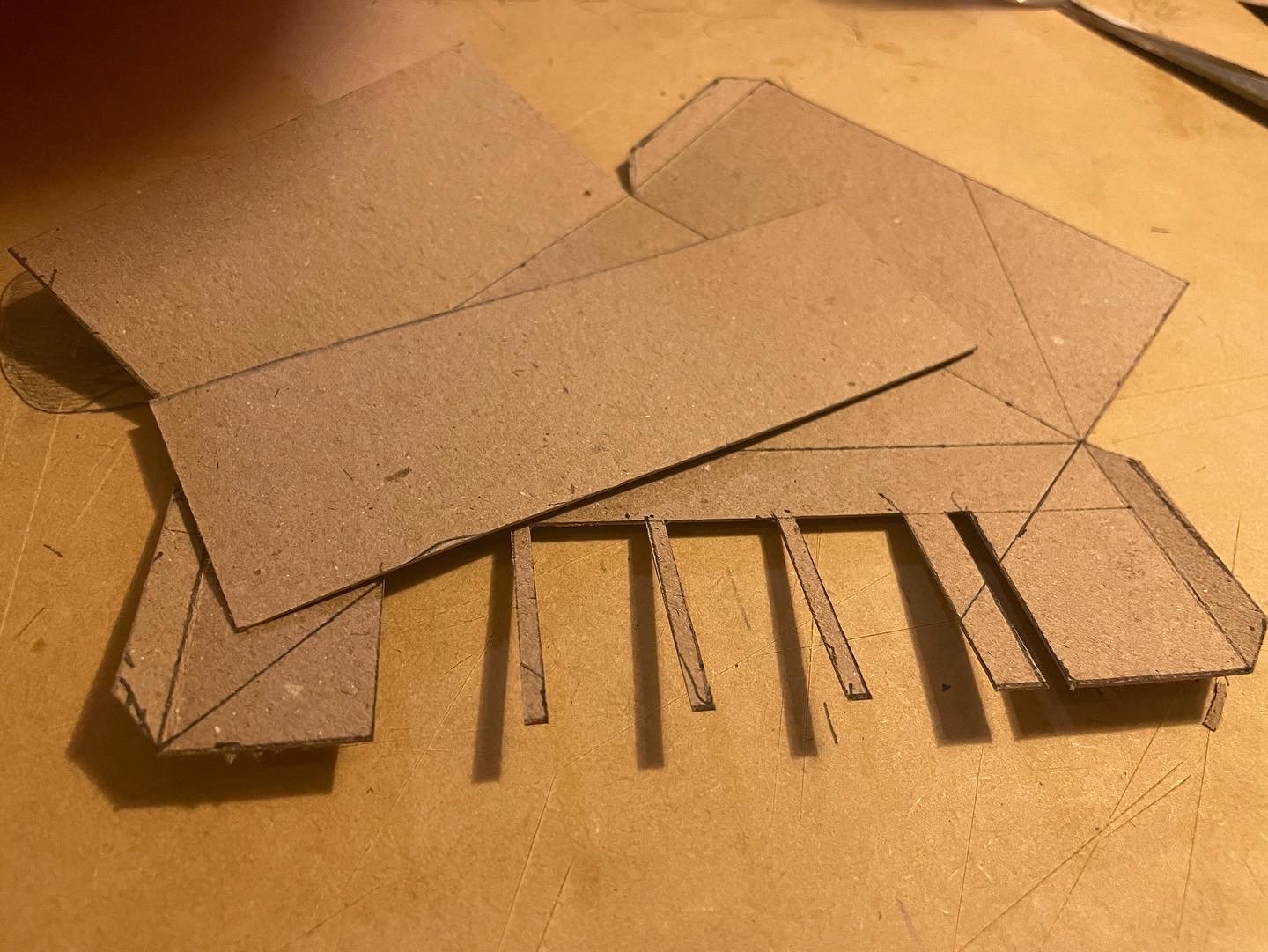

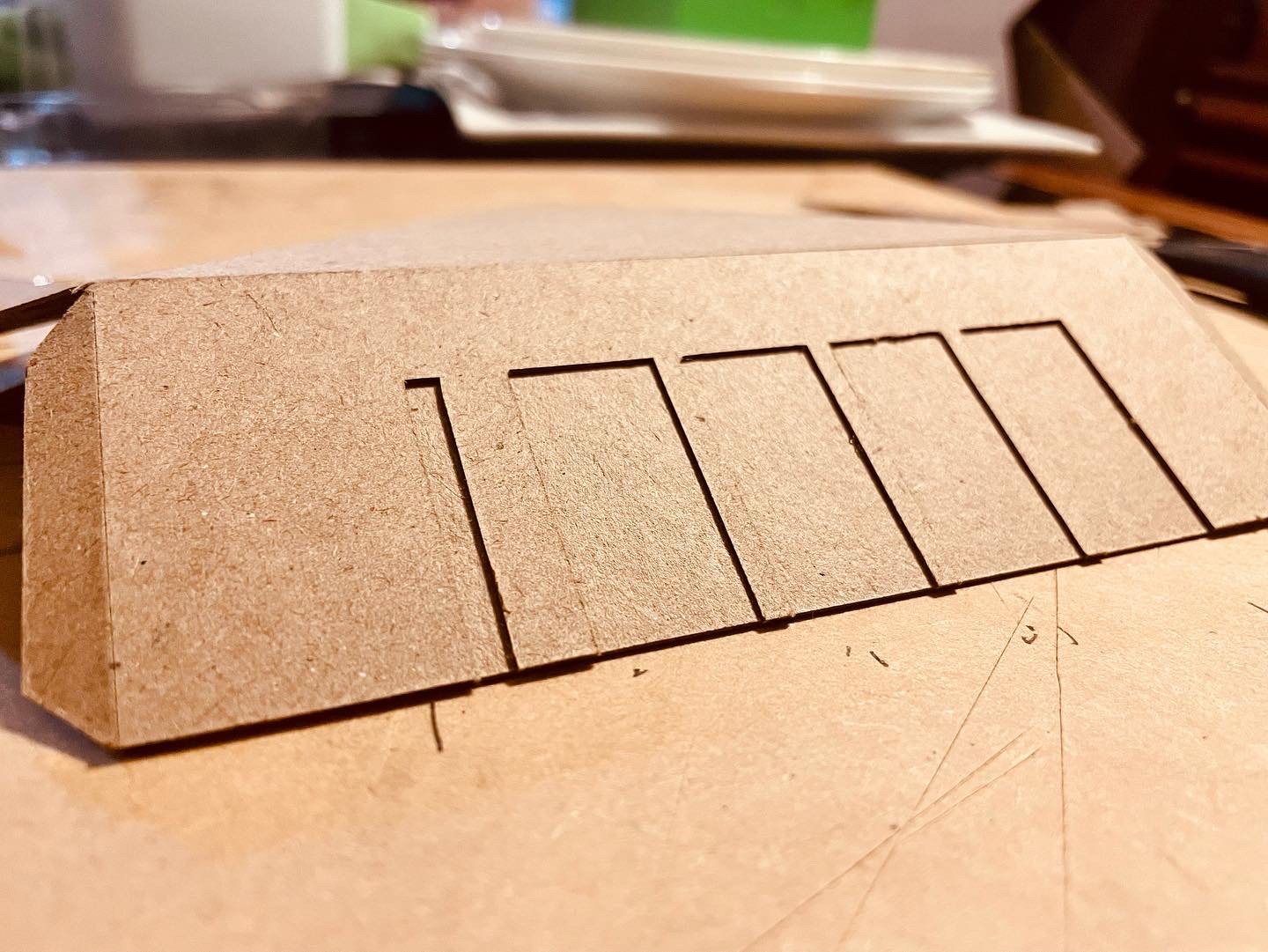

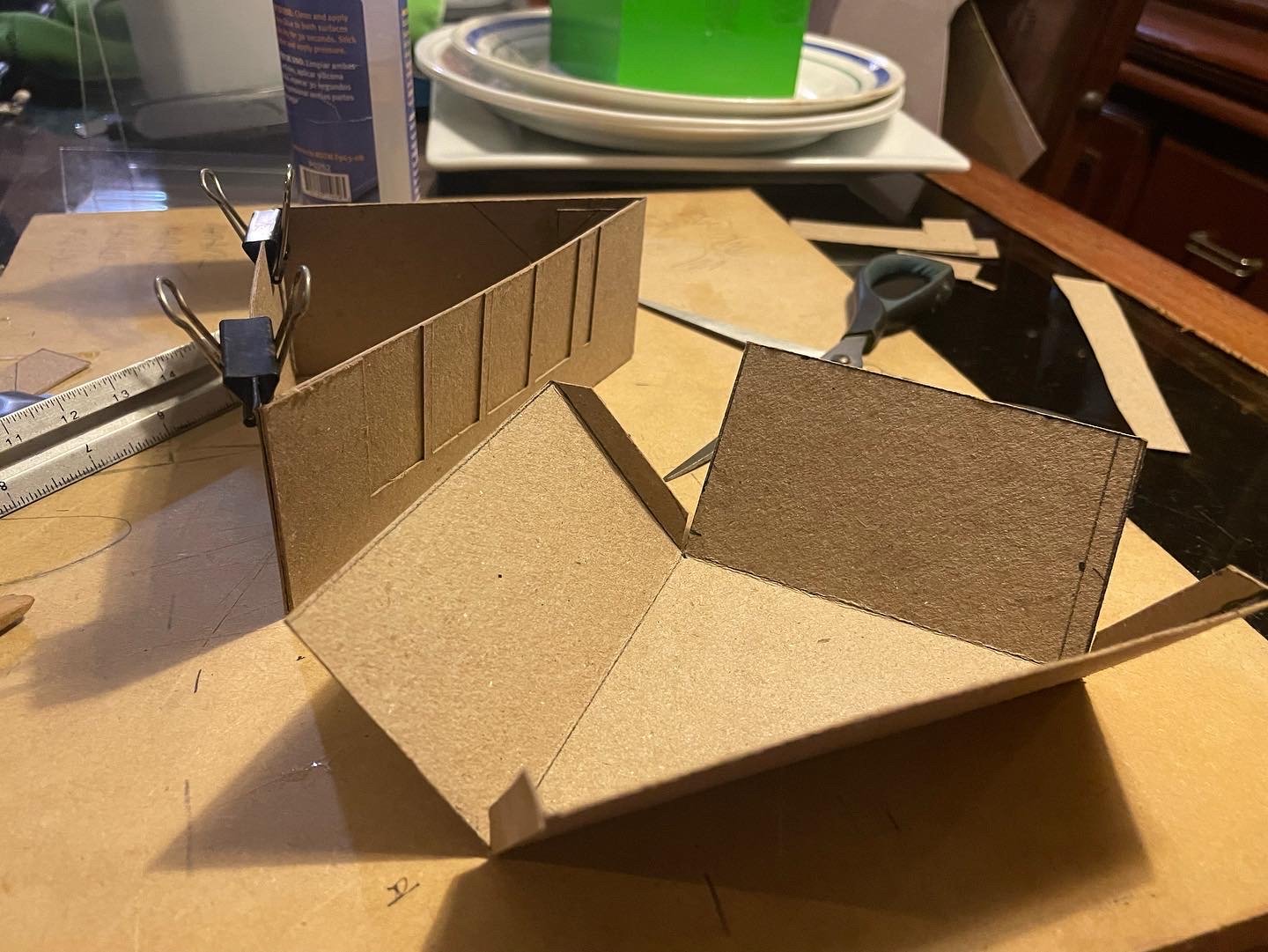

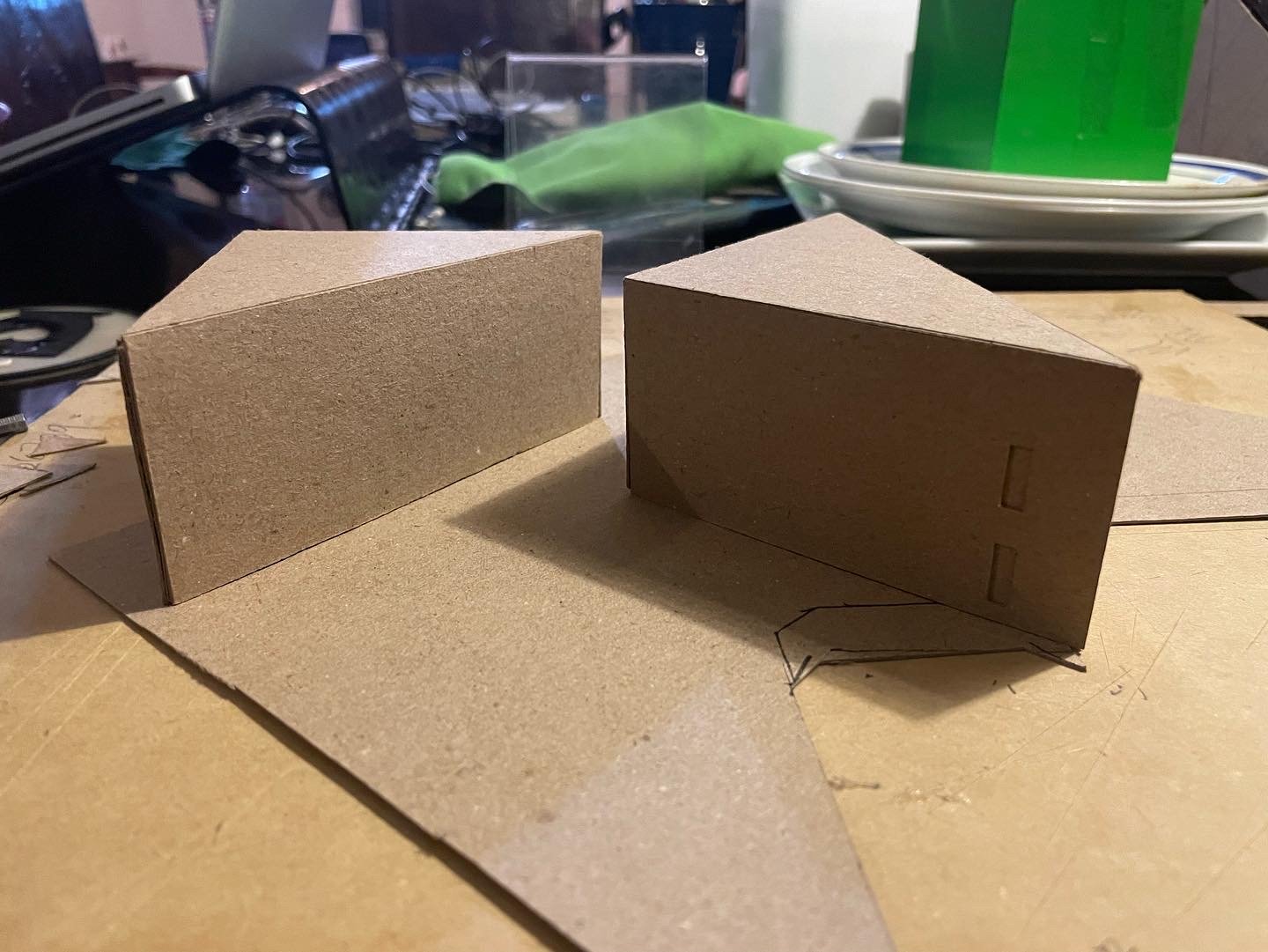

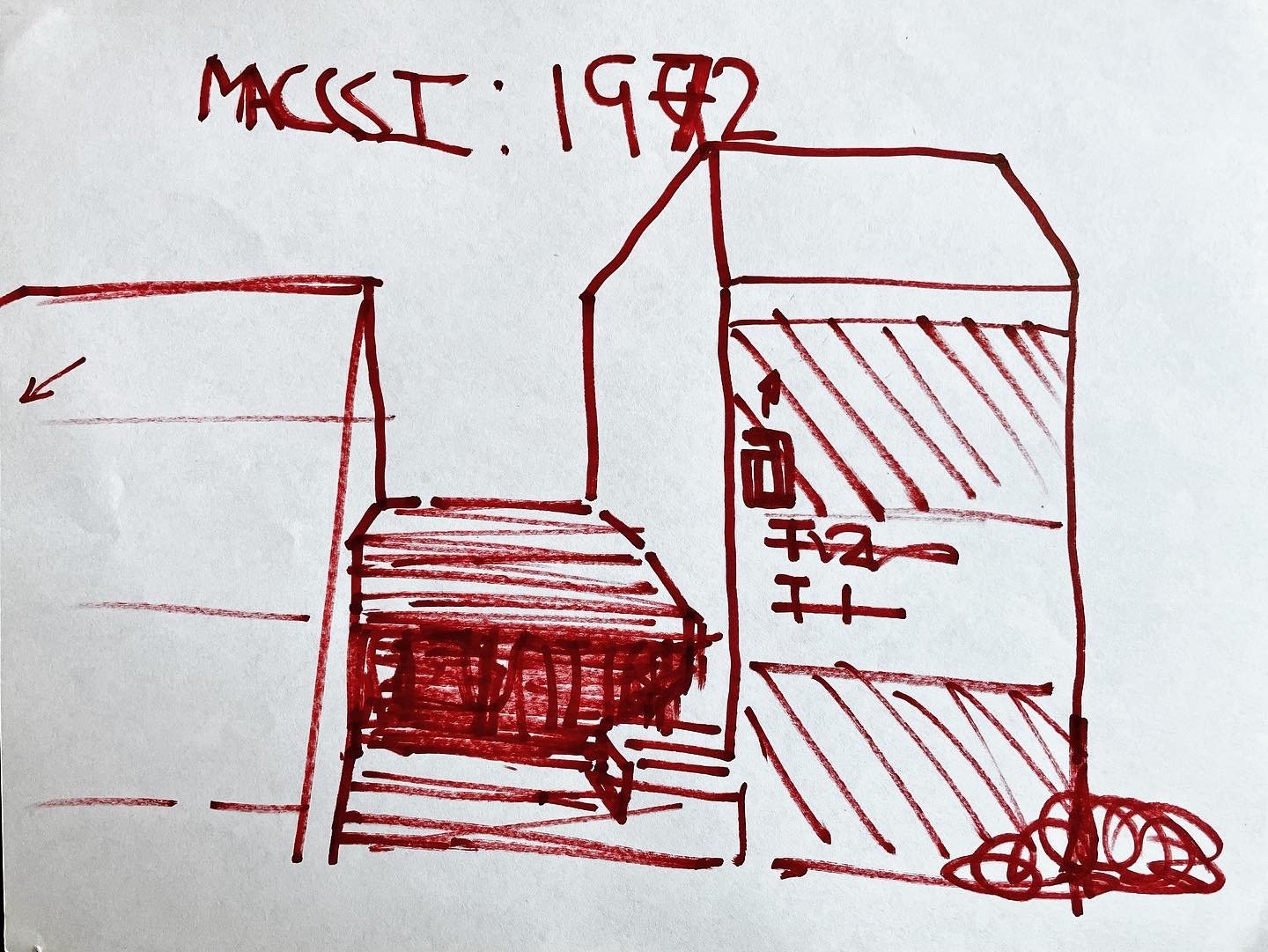

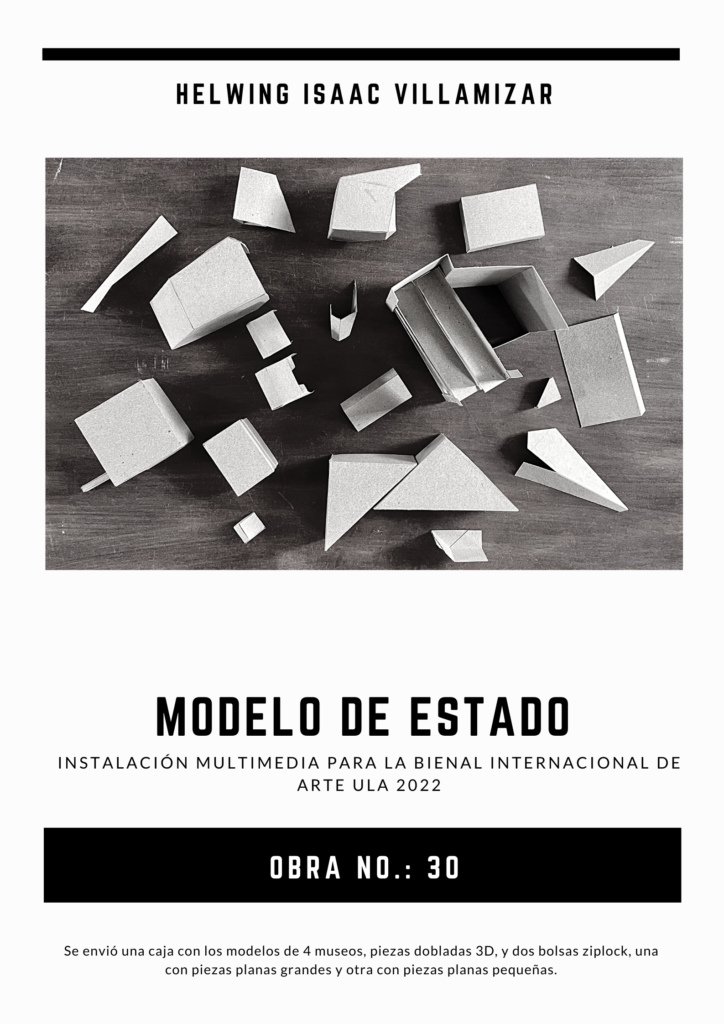

This long-term project includes more than a dozen scale models of various sizes and finishes of Venezuela’s most important art museums.

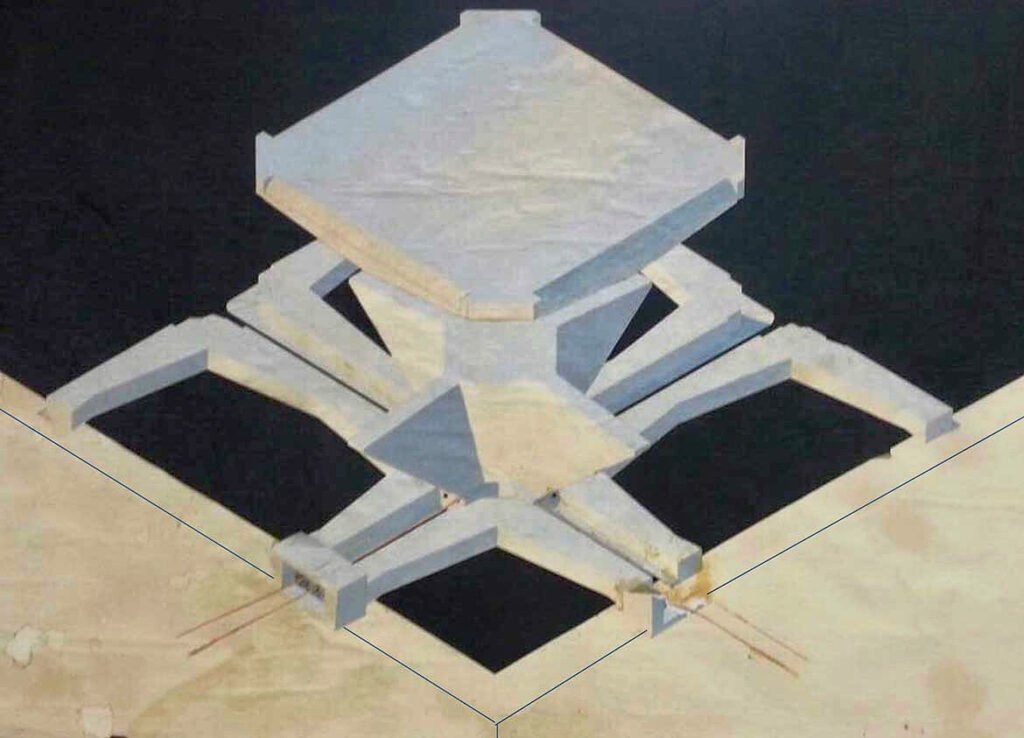

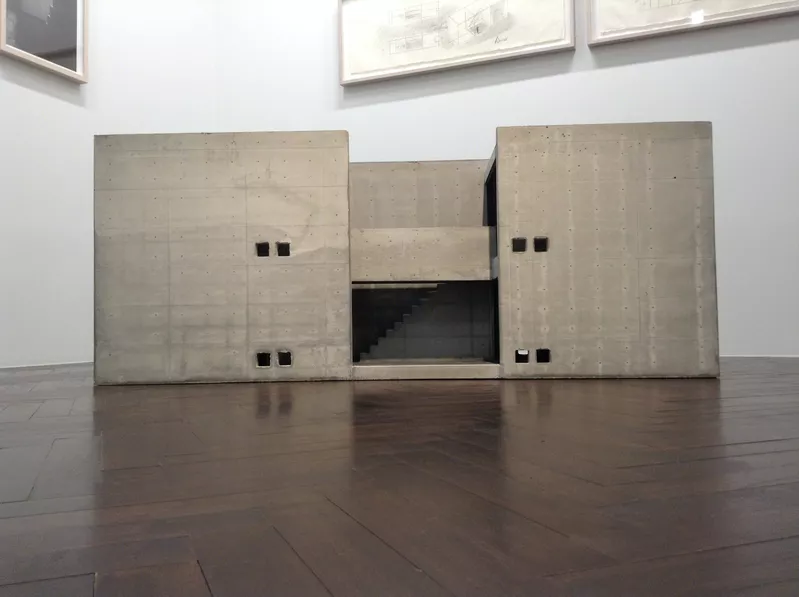

The models, built by myself and by architecture and film students, will be displayed in situ within a 3x3x3-meter floor-to-wall area where the 3D elements are to be placed either centered on tables or scattered throughout the main area (see images below), depending on the curators and the museography team.

As the maquettes will be drawn, photographed, and filmed in various settings and spatial configurations, these 2D works and videos will be mounted and projected or monitor-mounted on the wall of the allocated exhibition space.

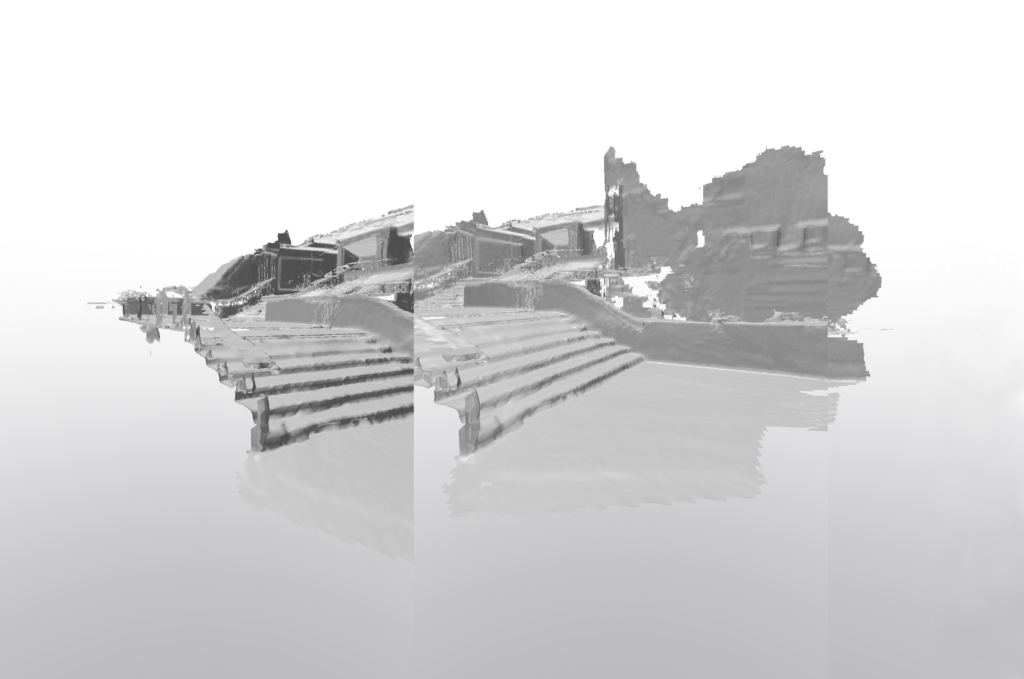

Additionally, 3D LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) scan images and videos of the documented museums will be shown alongside the films throughout the wall space.

Historical Context

The following is an extract from “Geometric abstract art in Venezuela and international politics geometry” by Zulian architect Elizabeth García-García that best summarizes the inception of the modern museum in Venezuela:

With the works of kinetic and abstract-geometric artists expressly commissioned as an identity for government buildings and public spaces, Venezuela would ultimately come to be recognized as the official home of kinetic art.

Venezuela consolidates an institutionalized artistic heritage, with the museum as an educational policy, in accordance with the guidelines of global actors such as UNESCO.

In the General Conference of UNESCO, II Meeting in Paris in 1960, Member States are invited to promote national cultural and artistic associations, linked to international organizations; to cooperate with UNESCO for the dissemination of the masterpieces of world art and the representative works of various literature; and to stimulate, through arts education, the dissemination of arts and literature, the cultural development of communities and international understanding. To this end, support is given to the efforts of states to promote arts education.

The Museum in Venezuela is a structural and structured strategy to propose a project of social transformation, through educational programs, as part of the social democratic thinking that translates into the thesis of “democratic humanism” of Master Prieto Figueroa.

This was the raison d’être of museums in Venezuela. According to Guevara, the idea of the museum is promoted as part of a “process of social transformation, (…) when you teach creative reasoning, you also teach to fight for other kinds of values” (Gaceta de Museos de Venezuela, 1989: 9).

As a result of this cultural policy, Venezuela would become known as the museum country of Latin America. The Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art, created in 1969 and opened to the public in 1973, was the first of the democracy -it joins the Museum of Sciences and the Museum of Fine Arts, both from 1940-, followed by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas “Sofía Imber” founded in 1973 and the National Art Gallery in 1976 -based in the Museum of Fine Arts-.

This marked the beginning of a period considered the greatest institutionalization of the cultural sector in Venezuela.